Pessimists, Optimists, Vulnerability, and Happiness

When someone asks whether I’m an optimist or a pessimist, I joke by repeating the saying that “the glass is half-empty and filled with cyanide.” Not exactly Schopenhauer I know, but awfully funny. On the whole, I *try* to think of myself as a levelheaded realist or pragmatist, but if I’m being honest with myself, I admit that I generally lean more towards negative scenarios.

A friend of mine this week posted a hilarious FB status update about her experience in answering an unknown caller on her mobile phone. My initial reaction was along the lines of what the heck… What are you doing?! Never NEVER answer an unknown caller! Here’s her story:

“Just got a call from an unknown number and I always say I won’t answer unknown numbers but I did anyway. The woman starts off with: Hello, is this [my friend’s name]? This is the State Department of Health. – Cue freaking panic. Then she lets me know I was selected to receive a gift card for filling out a survey back in November.”

She then explained her thought process and why she went into panic mode:

“Wait, why are they calling me? What happened? OMG, I’m going to die. I’m patient zero, wait, what? Epidemic. Huh. — It’s amazing how fast your brain goes through worst case scenarios in a split second.”

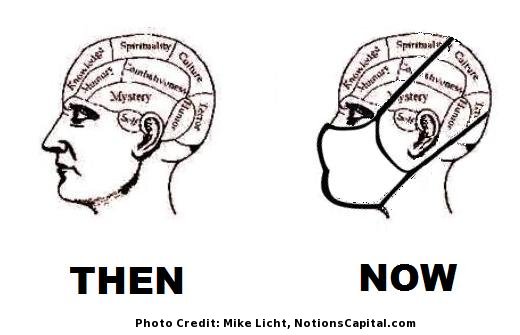

I totally agree with her conclusion, and I think this example perfectly illustrates how we often tend to jump to disastrous conclusions in our minds.

Some of us are born with naturally sunnier dispositions relative to others, but it doesn’t mean that we self-proclaimed pessimists realists can’t also find a level of happiness and fulfillment. I’m still insecure and admit that even though I’m entering middle age, a significant part of me still wants to be accepted and to be perceived as “cool” or someone who is regarded as a good skeptic critical-thinker. For whatever reason, nature vs. nurture, I’ve grown up learning to internalize that it’s definitely “not cool” or “intellectual” to be a serious adult, and still be super-optimistic. These days, you need to be a hater or a cynic in order to earn your street cred. Otherwise, you run the risk of being deemed delusional or someone who tries too hard. Why is that? I can’t quite put my finger on it. Maybe it’s a Seattle thing, or maybe it’s because negative badass people who don’t give a sh*t are perceived as cooler, more entertaining or fascinating given our culture’s (sometimes over) use of irony and sarcasm.

I’m currently reading Dr. Brene Brown’s latest book, Daring Greatly. I recently finished Chapter 4 entitled “The Vulnerability Armory,” which made me put down the book and exclaim, “Wow, she’s describing me to a tee!” In fact, a friend who originally recommended the book to me told me that when she read this same chapter, she immediately thought of me, and encouraged me to read the book. And she was absolutely right.

In Chapter 4, Brown talks about typical coping mechanisms (or armor) we often use to protect ourselves from the discomfort of vulnerability and authenticity. She describes the three main categories, or “shields” that many of us use: Foreboding Joy, Perfectionism, and Numbing. Most of us use multiple shields and she describes additional categories including “Cynicism, Criticism, Cool, and Cruelty” further on, but these are the three main categories she discusses in the chapter.

I’m an all-in foreboding joy type of person myself, which Brown describes as a continuum that runs from “rehearsing tragedy” to what she calls “perpetual disappointment.” She explains that “[i]n our culture of deep scarcity—of never feeling safe, certain, and sure enough—joy can feel like a setup… We’re always waiting for the other shoe to drop.” Many of us have programmed ourselves to try to limit our joys and disappointments by “beating vulnerability to the punch. We don’t want to be blindsided by hurt. We don’t want to be caught off-guard, so we literally practice being devastated or never move from self-elected disappointment.”

Foreboding joy a constant mental game that I subjugate upon myself so that I feel some semblance of control over outcomes I honestly don’t have any control over. And this goes for stupid little things like sporting event outcomes to big life crises. I’m constantly driven by a sense of scarcity and fear, and it’s my control-freak response to try to at least control my own emotions and reactions when I am truly and utterly powerless.

But foreboding joy doesn’t really work. No matter how many grisly images I might rehearse in my mind, if and when tragedy strikes, I will be utterly devastated and no amount of mental “practice” will prepare me for it. And constantly catastrophizing isn’t really a healthy shield to be lugging around throughout your life.

Brown goes on to reveal that the antidote to foreboding joy is practicing gratitude, and to simply “acknowledge how truly grateful we are for the person, the beauty, the connection, or simply the moment before us.” To combat foreboding joy with gratitude, Brown lists three ways we can practice gratitude in our everyday lives:

– Joy comes to us in moments—ordinary moments. We risk missing out on joy when we get too busy chasing down the extraordinary.

– Be grateful for what you have.

– Don’t squander joy.

I loved how Brown called out my personal tried-and-true defense mechanism, and offered solutions to combat what foreboding joy ultimately robs me of: fully engaging and enjoying the present, and living a life of abundance.

If you’ve been reading my blog for a bit, you’ll notice that I’m kind of a serious TED addict. TED speakers are amazing people who’ve accomplished amazing things. And they are charged with the task of delivering the best speech of their life in 20 minutes or less (no pressure.) So all of the talks range from very good to mind-blowing. But one of my favorite quotes in all of the TED talks I’ve watched over the years is revealed in Brown’s most recent talk: “You know what the big secret about TED is? I can’t wait to tell people this…. I guess I’m doing it right now. Um, this is like the failure conference. No, it is. You know why this place is amazing? Because very few people here are afraid to fail.” She hit upon something that we often forget and don’t emphasize. Even amazing, accomplished TED speakers have succumbed to amazing, accomplished failures. Wow.

Brown’s second TED talk is entitled “Listening to Shame,” and she outlines the ethos of her latest book, Daring Greatly, and I’d encourage you to watch it.

I understand that much of my personal internal pessimism/foreboding joy is self-stitched analytical armor against vulnerability. And I totally jive with the saying: if you set low expectations, you’ll never be disappointed or hurt. But I want to take a closer look at this kind of defensive armor and philosophy in a different context. So let’s look at what brain scientist, Dr. Tali Sharot says in her TED talk “The Optimism Bias” and the fallacies of low expectations based on her book The Science of Optimism.

Although Sharot comes at the question from a different angle relative to Brown, her findings reveal that in fact, while pessimists (aka: clinically depressed people) may be more realistic about outcomes, we humans are actually wired for hope. So she asks a central question as a brain scientist: “Hope isn’t rational, so why are humans wired for it?” She goes on to explore how and why pessimism (which I simply equate to behaviors like practicing foreboding joy) is NOT a good strategy for living a fulfilling life:

“The problem with pessimistic expectations, such as those of the clinically depressed, is that they have the power to alter the future; negative expectations shape outcomes in a negative way. Not everyone agrees with this assertion. Some people believe the secret to happiness is low expectations. If we don’t expect greatness or find love or maintain health or achieve success, we will never be disappointed. If we are never disappointed when things don’t work out and are pleasantly surprised when things go well, we will be happy. It’s a good theory — but it’s wrong. Research shows that whatever the outcome, whether we succeed or we fail, people with high expectations tend to feel better. At the end of the day, how we feel when we get dumped or win an award depends mostly on how we interpret the event.”

Mildly depressive people are realists vs. normal people. And without the optimism bias, we’d all be slightly depressed. But optimism and hope seem to be the better and healthier, more productive mindset. Having higher expectations actually makes us happier and more successful. And despite the fact that we might fail, by setting higher expectations for ourselves with hope, we tend to feel better.

Sharot goes on in her talk to explain three main reasons why setting low expectations is NOT a good theory in practice:

1) People with higher expectations are happier and more successful. Between High and Low Expectors, Low Expectors are less happy.

2) The pure act of anticipation makes us happy, regardless of outcome. We are willing to pay to wait. Ex: people overwhelmingly prefer Friday [to Sunday], because Friday brings with it the anticipation of the weekend ahead.

3) Optimism changes subjective reality, but it also changes objective reality. Optimism is directly correlated to success and better health.

Here’s Tali Sharot’s “The Optimism Bias” TED talk:

Finally, I’ll end with a wonderful and revealing chart from Sharot’s book that cites the work of behavioral economist Dr. Andrew Oswald who plots a universal U-shaped happiness curve. “From about the time we are teenagers, our sense of happiness starts to decline, hitting rock bottom in our mid-40s (middle-age crisis, anyone?). Then our sense of happiness miraculously starts to go up again rapidly as we grow older.”

In looking at Oswald’s U-shaped chart of satisfaction (n=70,000) it seems I’m approaching the nadir of the U-shaped chart, which might explain some of my current doom and gloom. But I’m now trying to strike a balance between emotional honesty and vulnerability, and having a more optimistic outlook.

I guess I’m learning that it’s more important to be happy and healthy rather than be right all the time. In the long run, optimism seems to trump realism.

Happy Friday! Enjoy your second-most beloved day of the week!

Very interesting and thought-provoking article, ATT! I’d like to add one distinction to

“expectations” – those of ourselves and those of others. I personally believe that we should set high expectations for ourselves when we set out to accomplish anything simple or ambitious, but I also I believe that we should try our best to lower (or even get rid of) our expectations of others. The two opposing aspects of expectations should be sufficient to make us happier.

Ah, yes, thank you for your distinction, and agree with you. Yes, in terms of expectations in this post, I was referring to the internal ones we set for ourselves. Expectations we set for others (our loved ones, partners, children) often end in tears…

Since it’s the season when many expats are on the move, I’m rather sad about some wonderful people moving away from Hong Kong and out of my day-to-day life. As a hedge against this current pain, I can feel myself emotionally distancing myself from them. More troubling, I can also feel myself emotionally distancing myself from many expat friends who aren’t moving away as a hedge against future pain.

I know I should simply embrace these transient friendships because many of them seem to last despite moves and distance, but sometimes I get so tired of saying goodbye.

Thanks for the reminder about the importance of outlook in shaping our lives and that it is more worthwhile to be optimistic.

Hi Jen, thanks for your honest sharing. Sounds like you’re entering into the middle of the expat goodbye/moving season, and it sounds pretty gutting to constantly have to say goodbye to dear friends. Totally get how you’re “hedging against future pain,” as I tend to do it too. But yes, it’s also good to remember that you now have friends all over the world to visit! 🙂 Hope all is well.

Great essay; it explores a human truth from a very contemporary perspective. The pursue of happiness seems to be a very American thing, or at least a first world preoccupation, which people can approach from optimistic or pessimistic perspective depending on character. Yes, I agree there are people who tend to be more pessimistic and have lower expectations. We assume that those people would find easy joy if they encounter a positive outcome. They don’t, even when they enjoy a relatively nice life. On the contrary, there is another part of humankind that is cheery and jolly and can find the “bright side of life” in the direst circumstances. Honestly, these people are irritating to me. Equilibrium is desirable. We gloomy people of the world need to be balanced by the hopeful bunch.

I agree with travelbypoints in that it’s best to keep expectations of others very low. I also agree with expatlingo in that those of us who move with every corporate wave tend to be more emotionally detached than others for fear of saying good bye to people we have come to love.

Hi Lisbeth, thank you for your insightful comments. I even think the word “happiness” is a little insufficient for what I’m trying to ultimately get at since for most of us, it’s often a fleeting emotion that is usually based on external circumstances. This might be semantics, but I think maybe some better words are “joy” or “contentment.” And from what I’ve been reading, a deep sense of joy and contentment is often and usually related to perseverance, and in many cases, to suffering and failure.

Thanks for bringing up the developed world’s preoccupation with success and happiness. We often think that the two go together sequentially, ie: 1) if we are successful, then 2) we will become happy. But once we’ve reached our marker for “success” we feel happy for about 1/2 a day, and then the goal posts move, and we strive to reach the next marker, leaving us unhappy and constantly paranoid or wanting. We NEVER reach happiness or sustained joy based on our success or achievements. This is the “never enough” culture that Brown and many others talk about. So I think I probably should have used a term that signifies a longer-term mindset, and maybe joy or contentment or a sense of peace are better words.

It’s hard to constantly invest in relationships and expat friendships that ultimately will end in a year or two, so I can totally understand how emotionally draining it can be, which is why I think there is some comfort in a virtual community. It’s definitely not the same, but it’s still a way to keep in touch w/friends and loved ones all over the world. I definitely still miss some of my best friends back in HK, and FB and Skype or WhatsApp help, and is better than nothing, so I’ll take it. Thanks for stopping by and for your comments!